Jökulhlaups in Alaska’s Wrangell-St. Elias National Park

A recent Smithsonian Magazine article gives some interesting insights to present-day Jökulhlaups (glacial outburst floods) that are but minuscule relatives of the cataclysmic Ice Age Floods. Iceberg Lake was on the edge of a western tributary of the Tana Glacier, but in 1999 the lake suddenly vanished. Dammed on its southern end by ice, the water, with persistently warming temperatures, had bored a hole under the ice and escaped through tunnels to emerge ten miles away and empty into the Tana River. The sudden drainage of a glacier-dammed lake is not uncommon. “Some lakes in Wrangell-St. Elias regularly drain,” Loso said. Hidden Creek Lake, for instance, near McCarthy, drains every summer, pouring millions of gallons through channels in the Kennicott Glacier. The water gushes out the terminus of the Kennicott, causing the Kennicott River to flood, an event called a jokulhlaup—an Icelandic word for a glacial-lake outburst flood. “The Hidden Creek jokulhlaup is so reliable,” said Loso, “it has become one of the biggest parties in McCarthy.” But the disappearance of Iceberg Lake was different, and unexpected. It left an immense trench in the ground, the ghost of a lake, and it never filled up again. The roughly six-square-mile mudhole turned out to be a glaciological gold mine. The mud, in scientific terms, was laminated lacustrine sediment. Each layer represented one year of accumulation: coarse sands and silts, caused by high runoff during the summer months, sandwiched over fine-grained clay that settled during the long winter months when the lake was covered in ice. The mud laminations, called varves, look like tree rings. Using radiocarbon dating, Loso and his colleagues determined that Iceberg Lake existed continuously for over 1,500 years, from at least A.D. 442 to 1998. “In the fifth century the planet was colder than it is today,” Loso said, “hence the summer melt was minimal and the varves were correspondingly thin.” The varves were thicker during warmer periods, for instance from A.D. 1000 to 1250, which is called the Medieval Warming Period by climatologists. Between 1500 and 1850, during the little ice age, the varves were again thinner—less heat means less runoff and thus less lacustrine deposition. “The varves at Iceberg Lake tell us a very important story,” Loso said. “They’re an archival record that proves there was no catastrophic lake drainage, no jokulhlaup, even during the Medieval Warming Period.” In a scientific paper about the disappearance of Iceberg Lake, Loso was even more emphatic: “Twentieth-century warming is more intense, and accompanied by more extensive glacier retreat, than the Medieval Warming Period or any other time in the last 1,500 years.” Loso scratched his grizzled face. “When Iceberg Lake vanished, it was a big shock. It was a threshold event, not incremental, but sudden. That’s nature at a tipping point.” One of the most startling, and devastating, consequences of this rapid melting of the ice was the Icy Bay landslide. The Tyndall Glacier, on the southern coast of Alaska, has been retreating so quickly that it is leaving behind steep, unsupported walls of rock and dirt. On October 17, 2015, the largest landslide in North America in 38 years crashed down in the Taan Fjord. The landslide was so enormous it was detected by seismologists at Columbia University in New York. Over 200 million tons of rock slid into the Taan Fjord in about 60 seconds. This, in turn, created a tsunami that was initially 630 feet high and roared down the fjord, obliterating virtually everything in its path even as it diminished to some 50 feet after ten miles. “Alder trees 500 feet up the hillsides were ripped away,” Anderson says. “Glacial ice is buttressing the mountainsides in Alaska, and when this ice retreats, there is a good chance for catastrophic landslides.” In other ranges, such as the Alps and the Himalaya, he says, the melting of “ground ice,” which sort of glues rock masses to mountainsides, can release enormous landslides into populated valleys, with devastating consequences. “For most humans, climate change is an abstraction,” Loso says when I meet him in his office, which is down a long, dark, heavily beamed mine building in Kennecott. “It’s moving so slowly as to be basically imperceptible. But not here! Here glaciers tell the story. They’re like the world’s giant, centuries-old thermometers.” Read the entire article “A Daring Journey Into the Big Unknown of America’s Largest National Park” online at SmithsonianMag.com

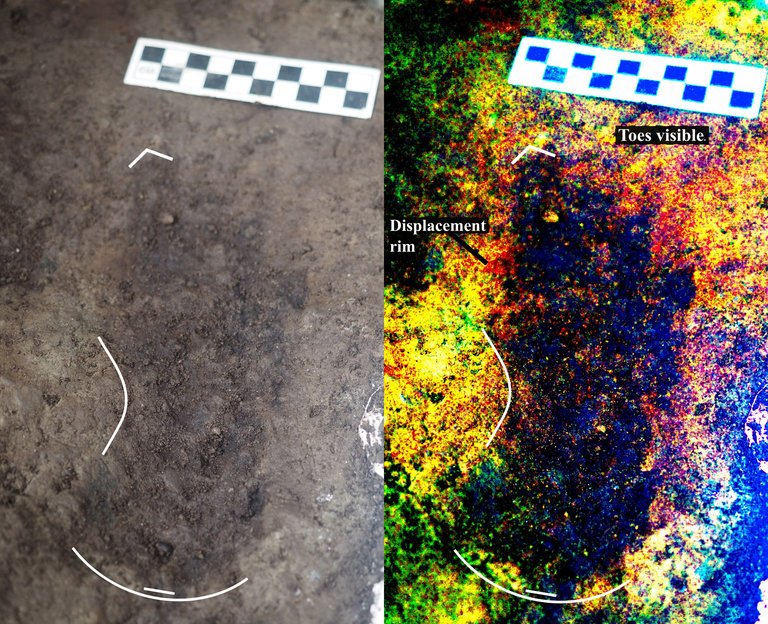

13,000 Year-Old Human Footprints Found on BC Island

Big feet. Little feet. A heel here. A toe there. A digitally enhanced photo of a footprint found at Calvert Island, British Columbia that researchers dated to 13,000 years old. Credit Duncan McLaren Stamped across the shoreline of Calvert Island, British Columbia, are 13,000-year-old human footprints that archaeologists believe to be the earliest found so far in North America. The finding, which was published Wednesday in the journal PLOS One, adds support to the idea that some ancient humans from Asia ventured into North America by hugging the Pacific coastline, rather than by traveling through the interior. “This provides evidence that people were inhabiting the region at the end of the last ice age,” said Duncan McLaren, an anthropologist at the Hakai Institute and University of Victoria in British Columbia and lead author of the study. “It is possible that the coast was one of the means by which people entered the Americas at that time.” Dr. McLaren and his colleagues stumbled upon the footprints while digging for sediments beneath Calvert Island’s beach sands. Today, the area is covered with thick bogs and dense forests that the team, which included representatives from the Heiltsuk First Nation and Wuikinuxv First Nation, could only access by boat. At the close of the last ice age, from 11,000 to 14,000 years ago, the sea level was six to ten feet lower. The footprints were most likely left in an area that was just above the high tide line. “As this island would only have been accessible by watercraft 13,000 years ago,” Dr. McLaren said, “it implies that the people who left the footprints were seafarers who used boats to get around, gather and hunt for food and live and explore the islands.” They found their first footprint in 2014. While digging about two feet beneath the surface in a 20-square-inch hole, they saw an impression of something foot-shaped in the light brown clay. In 2015 and 2016, they returned and expanded the muddy pit. They discovered several more steps preserved in the sediment. The prints were of different sizes and pointed in different directions. Most were right feet. When the team was finished they had counted 29 in total, possibly belonging to two adults and a child. Each was barefoot. The researchers think that after the people left their footprints on the clay, their impressions were filled in by sand, thick gravel and then another layer of clay, which may have preserved them. Using radiocarbon dating on sediment from the base of some footprint impressions, as well as two pieces of preserved wood found in the first footprint, Dr. McLaren and his team found them to be 13,000 years old. That would make them the oldest preserved human footprints in North America. “It’s not only the footprints themselves that are spectacular and so rare in archaeological context, but also the age of the site,” said Michael Petraglia, an archaeologist from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany who edited the paper for PLOS One but was not involved in the work. “It suggests an early entrance into the Americas.” Dr. Petraglia said the footprints also provided strong evidence for the coastal movement hypothesis and he added that they may have traveled the so-called “Kelp Highway,” a hypothesis that underwater kelp forests supported ecosystems down the North Pacific coast that helped ancient seafaring people hunt, develop and migrate. “The work is important because it shows the ‘real’ people, not just artifacts or skeletal remains,” said Steve Webb, a biological archaeologist at Bond University in Australia. “However, the footprints are limited in number and don’t shed light on activities or movement that tell us very much.” He added that future hunts for footprints should keep in mind that not everyone from this time period walked around barefoot. If anthropologists are too busy searching for soles, toes and arches, they might miss clues from those who wore animal skin shoes. Reprinted from New York Times – Earliest Known Human Footprints in North America Found on Canadian Island By NICHOLAS ST. FLEUR, March 28, 2018

ESA Maps a Lava Tube for Moon and Mars Expeditions

With all deference to the book and movie “The Martian”, wouldn’t you, as part of an interplanetary expedition, prefer to be protected from the radiation, micro-meteorites and extreme temperature fluctuations of the Moon or Martian surface? Though some of the hazards depicted in “The Martian” are way over-dramatized (the thin Martian atmosphere wouldn’t sustain the depicted raging storms), there are still hazards aplenty on the surface. So why not site your habitat in a cozy lava tube, protected from many of those surface nasties. At least that’s some of the reasoning behind a European Space Agency (ESA) effort to map a portion of Spanish lava tube in centimeter-scale detail as part of the ESA’s 2017 Pangaea-X campaign. Some chambers in the 8 km long La Cueva de los Verdes lava tube are large enough to hold residential streets and houses (or a prototype Martian research station/habitat). In less than 3 hours the cave research team mapped the lava tube using the smallest and lightest imaging scanner on the market and a wearable backpack mapper that collects geometric data without a satellite and synchronizes images collected by five cameras and two 3D imaging laser profilers. While the data is still being analyzed, ESA has released this ghostly fly-thru of a 1.3 km portion of the lava tube. Click the play button and prepare to take a pseudo-trip to Mars. So, the next time you visit a cave or lava tube, especially a large one, imagine yourself in a spacesuit on the Moon or Mars and realize that you’re actually an inner-space explorer. But don’t be too surprised at the creatures you may run into, they’re just other inner-space explorers too.

What’s Beneath Our Feet?

“Beneath Our Feet: Mapping the World Below” plumbs the depths of the question, “What’s beneath our feet?” through maps, images and archaeological artifacts. The exhibition explores nearly 400 years of maps and objects in an attempt to find out why and how humans imagine subterranean landscapes including caves, mines and water tables. Colorful and complicated images reflect the biases of long past and recent days and the concerns of their authors, including the United States’ desire to appropriate the natural resources of Native American lands and a 17th-century Jesuit priest’s attempt to use Scripture to create a framework for Earth’s geology. Catch the exhibition online, including a bibliography, reading lists and a 3-D tour of the Boston Public Library’s Norman B. Leventhal Map Center gallery itself. As you explore nearly 400 years of maps and images of the world below, you can compare the historical viewpoint with the modern, and see how we have advanced our perception and depiction of what lies beneath.

Indigenous Flood Stories from 14,000 Years Ago

On October 7th at Chief Timothy Park near Clarkston, WA at the latest Confluence Story Gathering, Thomas Morning Owl (Umatilla tribe) noted there are indigenous people’s stories of massive floods going back to 14,000 years ago. While he didn’t elaborate, it would be very interesting to have these stories shared as first-hand accounts of the Ice Age and/or Bonneville Floods. Confluence Story Gatherings are designed to elevate native voices in our understanding of the Columbia River system. This Confluence Story Gathering explored stories and perspectives from Nez Perce homelands, where a panel of indigenous thinkers and storytellers — Allen Pinkham, Sr. (Nez Perce), Thomas Morning Owl (Umatilla) and Jefferson Greene (Warm Springs) — shared their observations. Despite the strong winds, rain and even hail, the stories prevailed. Confluence Project is a community supported nonprofit that connects people to place through art and education. We work in collaboration with Northwest communities, tribes and celebrated artist Maya Lin to create reflective moments that can shape the future of the Columbia River system. We share stories of this river through six public art installations, educational programs, community engagement and a rich digital experience. The six projects span 438 miles from the mouth of the Columbia River to the gateway to Hell’s Canyon, with sites in both Oregon and Washington. These are “teachable places,” transformed and reimagined to explore the confluence of history, culture and ecology in our region. Each work references a passage from the Lewis and Clark journals as a snapshot in time, while comparing it with the deeper story.

Killer Floods – A New Nova Video on PBS

Discover how colossal floods transformed the ancient landscape. All over the world, scientists are discovering traces of ancient floods on a scale that dwarfs even the most severe flood disasters of recent times. What triggered these cataclysmic floods, and could they strike again? In the Channeled Scablands of Washington State, the level prairie gives way to bizarre, gargantuan rock formations: house-sized boulders seemingly dropped from the sky, a cliff carved by a waterfall twice the height of Niagara, and potholes large enough to swallow cars. Like forensic detectives at a crime scene, geologists study these strange features and reconstruct catastrophic Ice Age floods more powerful than all the world’s top ten rivers combined.

The Road Not Taken

Robert Frost finished his poem “The Road Not Taken” with this verse: I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood, and I— I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference. As our President Gary Ford has stated before, one of the best things we do as chapters is bus tours. And what we get to do on our tours is take the road less traveled. On this year’s fall bus tour, our chapter took a loop around the asymmetrical anticline Saddle Mountains of the Yakima folds in central Washington. It began with a run on the Ice Age Floods Geologic Trail through the Drumheller Channels but much of the trip was on the road less traveled. This included a narrow gravel road that took us to the base of the Corfu landslide complex, the ghost town of Corfu and down a section of the diverted Ice Age Columbia River valley before we got back to the main highway to pass through Sentinel Gap for our lunch and tour at the Gingko Forest Winery. In the afternoon after passing around and on the Priest Rapid bar, viewing two more landslides on Umtanum Ridge, and a look at the historic “B” reactor on the Hanford Reservation, we once again took the wash boarded gravel road less traveled and climbed to the summit of the Saddle Mountains. This was the highlight of the trip for most of the forty adventurers as from there, we could look down upon most of the sights we had already traveled. On this tour, many of the “locals” were visiting areas in their backyard for the first time. Yes, traveling the road less taken makes all the difference. There are other great flood sites in our area that are on roads that tour buses can’t negotiate. Our chapter will soon be addressing this issue to see how we can take people on these roads. by Lloyd Stoess, President – Palouse Falls Chapter

The Columbia River Gorge Eagle Creek Fire – Ruin or Renewal?

I’ve found there is huge public interest and concern about the catastrophic effects of the Eagle Creek Fire on the Columbia River Gorge. Pictures of ridgeline after ridgeline enveloped in bright orange fire, trees bursting into towering flames, and the choking smoke that filled valleys throughout the Pacific Northwest are truly a hellish image of Armageddon visited on the entire area. But, while the temporary loss of recreational trails and green forest aesthetics, and the increased potential for landslides and falling snags are inconvenient and even somewhat dangerous, the truth is that the recent fires have not ruined the natural areas of the West and the Gorge in particular, but instead have refreshed and renewed them. This past summer I’ve been interpreting geology for a new Columbia Gorge Master Naturalist Program, working beside forest ecology experts who are extremely optimistic regarding the effects of the Eagle Creek Fire. One of those experts, wildlife habitat expert Bill Weiler, writes, “Life will return to burned areas in short order. Fungi are already crawling around in the ashes of the fire, laying the foundation for soil that will support the plants that will constitute the early stage of the forest’s re-growth—a time when heat from the fire and sunlight newly reaching the ground in the absence of a canopy encourages a new crop of plants to firm up the soil structure that will allow gigantic trees to thrive. And ash is nature’s fertilizer. Plant blight, disease and insects are reduced or eliminated by burns. Mineral soil is the compost that Douglas fir seedling roots need to grow. “Dead trees” or snags are full of life.” In a typical forest fire a third of the trees will be scorched and dead, a third will be moderately to severely damaged, and a third will be essentially unscathed. Reports from the Eagle Creek Fire describe that fire as a discontinuous “mosaic burn” with much less devastation even than the typical forest fire burn. There is a broad consensus among scientists that we have considerably less fire of all intensities in our Western U.S. forests compared with natural, historical levels, when lightning-caused fires burned without humans trying to put them out. Early in the 20th century, before fire suppression became the norm, the average annual burn area in the western states was over 25 million acres, compared to a recent average of 4-6 million acres. According to Oregon State University Professor John Bailey, a century’s worth of suppressing wildfire in the United States has created conditions, especially in the West, that will ensure longer fire seasons because of longer, drier and hotter summers. Those conditions point to the need for “actively managed” forests which could include more deliberately set and managed prescribed fires. “Easily two-thirds or more of the Gorge fire is really good ecological fire,” Professor Bailey said, “the fire does some of the fuel management for us.” There is an equally strong consensus among scientists that fire is essential to maintain ecologically healthy forests and native biodiversity. This includes large fires and patches of intense fire, which create an abundance of biologically essential standing snags and naturally stimulate regeneration of vigorous new stands of forest. These areas of “snag forest habitat” are ecological treasures, not catastrophes, and many native wildlife species depend on this habitat to survive. More than 260 scientists wrote to Congress in 2015 noting that snag forests are “quite simply some of the best wildlife habitat in forests. ” Much of the Eagle Creek Fire burn area is closed to civilian activities due to the danger from flare-ups, rock slides and falling snags. The fire is less than 50% contained due to the ruggedness and inaccessibility of much of the area. Though it is still burning it is not expected to flare-up again until Winter rains and snow completely douse the embers.

Castle Lake Basin

Castle Lake fills a plunge-pool at the base of a 300-ft tall cataract at the opposite (east) end of the Great Cataract Group from Dry Falls, above the east end of Deep Lake. A set of steel ladders put in place during the construction of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project allow for a safe descent into the basin. In the basin are great views of giant potholes, the flood-sheared face of Castle Rock, as well idyllic Deep Lake. The Castle Lake Basin lies along the east end of the Great Cataract Group. At the base of the cataract is lovely blue-green Castle Lake plunge pool nestled into the rock bench below. Castle Lake lies within a single recessional cataract canyon eroded down to a flood-swept, pothole-studded rock bench that stands 100 feet above Deep Lake. This is the same rock bench of Grande Ronde Basalt where dozens of potholes occur at the opposite (western) end of Deep Lake. Castle Rock itself is an isolated butte along the west side of the Castle Lake basin. It is a faceted butte escarpment nearly sheared off by monstrous flood forces moving across the cataract.

Frenchman Coulee Drone Video

Bruce Bjornstad is at it again with his awesome Ice Age Floodscapes drone videos, this one from Frenchman Coulee. Watch it below and visit his Ice Age Floodscapes YouTube channel.for many more.