Lake Lenore Caves – Lower Grand Coulee

Tucked into the Lenore Canyon are the Lake Lenore Caves. Along with much of the eastern half of the state, Lenore Canyon was formed during the Missoula floods at the end of the last Ice Age, over 13,000 years ago. The glacial flood waters crashed down the canyon, carving through the basalt that makes up the sheer rock walls, creating coulees, ridges, cliffs, plateaus, rock slides, caves and a series of lakes. The caves themselves are shallow, created during the Great Missoula flood as water pulled chunks of basalt from the walls of the coulee. Post-flood weathering created talus slopes that furnished easy access and temporary overnight camps and storage for at least 5,000 years for hunters and gatherers from villages located elsewhere in the Grand Coulee and along the Columbia River and its tributaries. It is still used today for certain Native American religious ceremonies. It is easy to see why the caves were chosen as a cozy place to stay, as the depth provided plenty of shelter from the elements, while not going so deep that light couldn’t reach the back corners. It is often quite warm and breezy outside, but in the caves it is cool and calm. A well-marked 1.2-mile out-and-back trail leads from the parking area to some of the caves. It is generally considered an easy route that takes an average of 31 min to complete. This is a popular trail for hiking and walking, but you can still enjoy some solitude during quieter times of day. The best times to visit this trail are March through November. Dogs are welcome, but must be on a leash. The coulee walls in this area are made up of Grande Ronde Basalt flows overlain by the Frenchman Springs and Roza members of the Wanapum Basalt. The lower (colonnade) and upper (entablature) cooling units of individual flows are visible in the coulee walls. Flow unit contacts are sometimes complex to interpret. Some flows pinch out against older flows, some are perhaps due to flows covering an irregular topographic surface on the underlying flow, some may be filling of shallow valleys, and some multiple layers may be pulses of lava from the fluid interior pushing out over the partially formed entablature of a previous lava pulse.

Grand Coulee – Geology of the Entire 50 miles

The 50-mile-long Grand Coulee should be on everyone’s bucket list for a “must see” feature. The immense power of the forces that created the Coulee are apparent to those who read the evidence recorded in its rocks and landforms. How did the Coulee form? Why did it form here? What do features like Steamboat Rock, Northrup Canyon, Dry Falls, and the Ephrata Fan tell us about the geological forces that created the Grand Coulee? This presentation will be made May 1, 2023 beginning at 7:00 pm, via Zoom _ https://us02web.zoom.us/j/82985244730 Dr Gene Kiver is professor Emeritus of Geology, Eastern Washington University. He studied alpine glaciation in the Rocky Mountains before moving to Washington State and discovering that J Harlen Bretz had correctly interpreted the bizarre landforms of the Channeled Scabland. Gene taught geology at Eastern Washington University for 34 years. He co-authored “On the Trail of Ice Age Floods” with Bruce Bjornstad that describes the flood history of the northern flood routes of the Missoula Floods. In addition, he authored/co-authored the book “Washington Rocks” and several other books. One item in particular is “Tour Guide Interstate 90 East Tour: Seattle to Spokane” (2007). A CD narration of the people and places as defined by the title. Of the 51 tracks, Dr. Kiver narrates 4 on the Geology of I-90. The Chapter webmaster has ordered it and will update this post after listening to the recording. I bring this up as many of our lectures are about or by people who explored or are exploring the geography of the Ice Age Floods. Look on Amazon under “Eugene Kiver” for this and other books.

Uncovering a Columbian Mammoth

There’s a Columbian Mammoth hiding out in Coyote Canyon down Kennewick way, and MCBONES Research Center Foundation is working to uncover his/her hiding place. For a small contribution you can tour this hide-and-seek site, or you can volunteer to help uncover the hidden mammoth. Sound interesting? Find out more in this short video produced by Mark Harper of “Smart Shoot“, or visit the MCBONES website. The Mid-Columbia Basin Old Natural Education Sciences (MCBONES) Research Center Foundation provides local K-12 teachers and their students, as well as other volunteers, an opportunity to actively participate in laboratory and field-based research in paleontology, geology, paleoecology, and other natural sciences primarily within the Mid-Columbia Region of southeast Washington State.

6 New ‘Nick On The Rocks’ Episodes

6 new short episodes of ’Nick On The Rocks’ aired on PBS this past winter! Each of these gems are short enough to be taken in by even the busiest of us, and yet have enough information to whet the appetite of even the most intensive of us. Nick is masterful in his presentations and who he draws in to help. Watch them all, you won’t be disappointed. Lake Chelan – Battle of the Ice Sheets (w/ Chris Mattinson) Click HERE to watch. 5 minutes. Chasing Ancient Rivers (w/ Steve Reidel) Click HERE to watch. 5 minutes. Seattle Fault (w/ Sandi Doughton) Click HERE to watch. 5 minutes. Bridge of the Gods Landslide (w/ Jim O’Connor) Click HERE to watch. 5 minutes. Columns of Basalt Lava Click HERE to watch. 5 minutes. Ancient Volcanoes in the Cascades (w/ Daryl Gusey) Click HERE to watch. 5 minutes.

Castle Lake Basin

Castle Lake fills a plunge-pool at the base of a 300-ft tall cataract at the opposite (east) end of the Great Cataract Group from Dry Falls, above the east end of Deep Lake. A set of steel ladders put in place during the construction of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project allow for a safe descent into the basin. In the basin are great views of giant potholes, the flood-sheared face of Castle Rock, as well idyllic Deep Lake. The Castle Lake Basin lies along the east end of the Great Cataract Group. At the base of the cataract is lovely blue-green Castle Lake plunge pool nestled into the rock bench below. Castle Lake lies within a single recessional cataract canyon eroded down to a flood-swept, pothole-studded rock bench that stands 100 feet above Deep Lake. This is the same rock bench of Grande Ronde Basalt where dozens of potholes occur at the opposite (western) end of Deep Lake. Castle Rock itself is an isolated butte along the west side of the Castle Lake basin. It is a faceted butte escarpment nearly sheared off by monstrous flood forces moving across the cataract.

Frenchman Coulee Drone Video

Bruce Bjornstad is at it again with his awesome Ice Age Floodscapes drone videos, this one from Frenchman Coulee. Watch it below and visit his Ice Age Floodscapes YouTube channel.for many more.

Lake Lewis High Water Markers Installed

In April, 2017, Lake Lewis members George Last and Bruce Bjornstad worked with Friends of Badger volunteers Jim Langdon (Trail Master) and David Beach to install Markers showing the Lake Lewis high water marks on Badger and Candy Mountains near Richland, Washington. The Lake Lewis Chapter donated $300 to the Friends of Badger Mountain to purchase the two faux erratics engraved with “Lake Lewis Maximum Elevation 1250 Feet”. One of the markers was installed along the Sagebrush Trail on Badger Mountain, and the other along the Candy Mountain Trail. It was a glorious day!

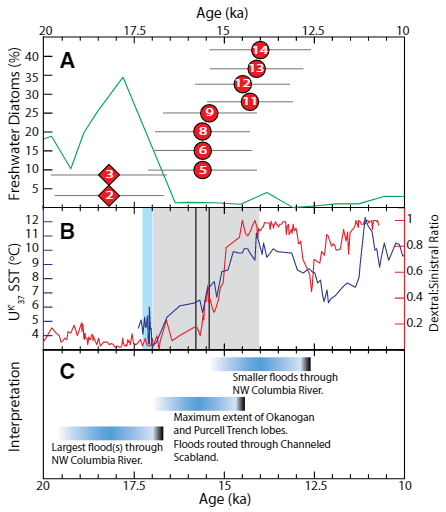

Beryllium-10 dating of late Pleistocene megafloods and Cordilleran Ice Sheet retreat

Balbas et. al. use cosmogenic beryllium-10 dating methods to further constrain the timing of ice sheet retreat, as well as the potential pathways for megafloods from both Lake Missoula and Lake Columbia. Read this fascinating Geology article summarizing their findings. Balbas2017 – Missoula Flood Chronology In summary, our new chronological information suggests the following: (1) Blockage of the Clark Fork river by the Purcell Trench lobe by ca. 18.2 ka, resulting in Missoula floods following the Columbia River valley. (2) Blockage of the Columbia River valley by the Okanogan lobe before 15.4 ± 1.4 ka, which shunted Missoula flood water south across the Channeled Scablands. (3) The final Missoula floods at ca. 14.7 ± 1.2 ka, signaling retreat of the Purcell Trench lobe from the Clark Fork valley, yet these floods entered a glacial Lake Columbia still impounded by the Okanogan lobe. (4) Down-Columbia floods at ca. 14 ka from breakouts of glacial Lake Columbia, signaling the retreat and final damming of the Columbia Valley by the Okanogan lobe

Washington’s Ice Age Floods – ESRI Story Map

The Washington Geological Survey (formerly the Division of Geology and Earth Resources) has just released an ESRI story map about the Ice Age Floods in Washington. The story map: “tells the story of cataclysmic outburst floods that shaped the landscape of the Pacific Northwest during the last ice age. With imagery, maps and video, this story map follows the devastating deluge of the Missoula floods as it tore across the landscape, from its origins in western Montana to its terminus at the Pacific Ocean. Sites along the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail are featured, with an emphasis on flood features in Washington State.” Entitled Washington’s Ice Age Floods, it is best viewed on a desktop or laptop computer. Mobile devices will not show all of the content. It is navigated by scrolling your mouse through the slides. There are a few animated sections that may take a second or two to load. [weaver_iframe src=’https://wadnr.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=84ea4016ce124bd9a546c5cbc58f9e29′ height=600 percent=100]

Williams Lake Cataract Video

Williams Lake Cataract is an ancient, dry waterfall left behind along the Cheney-Palouse Scabland Tract in eastern Washington after Ice Age flooding recessionally ripped out underlying basalt to produce this massive cataract. Video produced by Bruce Bjornstad, Ice Age Floodscapes