Have you ever thought about the how the weight of the ice-age Cordilleran ice sheet might affect the underlying Earth’s crust. There is strong evidence that the crust was depressed hundreds of feet beneath the ice, and since the crust is relatively thin and rigid over a plastic aesthenosphere, that also caused the crust for some distance beyond the ice margins to tilt toward the ice sheet.

Have you ever thought about the how the weight of the ice-age Cordilleran ice sheet might affect the underlying Earth’s crust. There is strong evidence that the crust was depressed hundreds of feet beneath the ice, and since the crust is relatively thin and rigid over a plastic aesthenosphere, that also caused the crust for some distance beyond the ice margins to tilt toward the ice sheet.

A new modeling study explored how changes in topography due to the solid Earth’s response to ice sheet loading and unloading might have influenced successive megaflood routes over the Channeled Scablands between 18 and 15.5 thousand years ago. The modeling found that deformation of Earth’s crust may played an important role in directing the erosion of the Channeled Scabland. Results showed that near 18 thousand year old floods could have traversed and eroded parts of two major Channeled Scabland tracts—Telford-Crab Creek and Cheney-Palouse. However, as the ice-age waned and the ice sheet diminished 15.5 thousand years ago, crustal isostatic rebound may have limited megaflood flow into the Cheney–Palouse tract. This tilt dependent difference in flow between tracts was governed by tilting of the landscape, which also affected the filling and overspill of glacial Lake Columbia directly upstream of the tracts. These results highlight one impact of crustal isostatic adjustment on megaflood routes and landscape evolution.

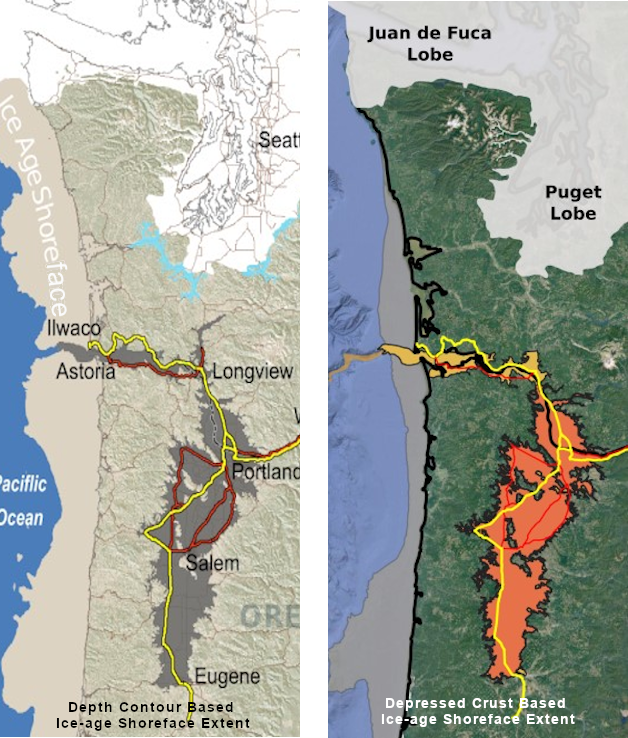

Other studies have shown that relative ice-age sea levels were over 300 feet lower worldwide due to the volume of water locked up in ice sheets. Typical depictions of the shoreface extent are generally based on a 300 ft. depth contour, but there is strong evidence that shorelines were up to 200+ ft. higher than present day in marine areas adjacent to ice sheets, again because the crust was depressed by the weight of the ice sheer. A more accurate representation might show a much narrower shoreface in ice-free areas nearer to the ice sheet margin.

However, in the Haida Gwaii Strait at the margin of the ice sheet the lower thickness of the ice sheet meant that local shorelines were as much as 550 feet lower than they are today. This was because the much greater thickness of the center of the ice sheet served to push upwards areas at the edge of the continental shelf in a crustal forebulge. It is now widely thought that these emergent ice-free land areas might have provided a viable coastal migration corridor for early peoples making their way to the Americas from Asia during the Pleistocene.