ICYMI (in case you missed it) — Floodwaters rise more than 1,000 feet as they slam into the Columbia River Gorge from the east. The torrent blasts through the narrows at 60 mph, carrying truck-size boulders and house-size icebergs. Reaching Portland, water loaded with gravel and dirt roils to a depth of 400 feet, leaving tiny islands at the summits of Mount Tabor and Rocky Butte.

Geologists have spent decades piecing together evidence to tell the story of the great Missoula floods that reshaped much of Oregon and Washington between 18,000 and 15,000 years ago.

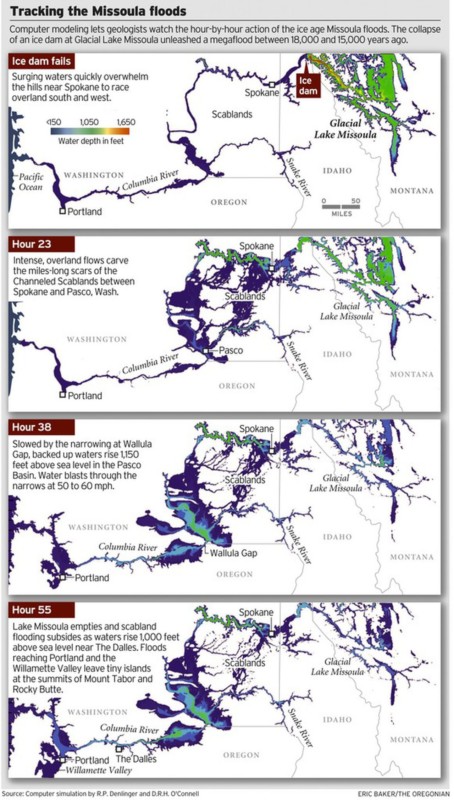

Now scientists have found a way to travel back in time to watch the megafloods unfold, in a virtual bird’s eye view. Their computer simulation displays the likely timing and play-by-play action, starting with the collapse of an ice dam and outpouring of a lake 200 miles across and 2,100 feet deep.

The computer model, developed by Roger Denlinger with the U.S. Geological Survey in Vancouver and Colorado-based geophysicist Daniel O’Connell, is filling gaps in scientific explanations of the floods and the baffling landforms they left, including the fabled Channeled Scablands — scars hundreds of miles long cut into the bedrock of eastern Washington and visible from outer space. The simulations also may help settle a lingering scientific controversy about what caused the repeating ice-age catastrophes.

The computer model, developed by Roger Denlinger with the U.S. Geological Survey in Vancouver and Colorado-based geophysicist Daniel O’Connell, is filling gaps in scientific explanations of the floods and the baffling landforms they left, including the fabled Channeled Scablands — scars hundreds of miles long cut into the bedrock of eastern Washington and visible from outer space. The simulations also may help settle a lingering scientific controversy about what caused the repeating ice-age catastrophes.

“It’s just really powerful visualization that gives a sense of the scale of the floods, how they came down through the channel system and backed up the big tributary valleys,” said Jim O’Connor, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Portland who has written extensively on the Missoula floods. He said the modeling work provides the first “really good information” on the timing of events.

During the last ice age, a continent-spanning ice sheet built from massively expanded glaciers descended from the Canadian Rocky Mountains to reach deep into Washington, Idaho and Montana. Glacial Lake Missoula formed behind a miles-long dam of ice across what is now the valley of the Clark Fork and Pend Oreille rivers running from Montana to northeast Washington. The dam formed and collapsed dozens of times over a span of three thousand years.

In the simulation of one of the largest possible floods, raging water quickly overwhelms the hills near Spokane and races overland to the south and west. The intense, overland flows carve the miles-long scars of the scablands between Spokane and Pasco, Wash.

Thirty-eight hours later, swirling, mud-darkened waters converge at the narrowing of the Columbia at Wallula Gap, where the backed-up flow rises 850 feet above river level (1,150 feet above sea level). An immense volume of water blasts through the narrows at fire-hose velocity. Flow exceeds 1.3 billion gallons per second — a thousand times greater than the Columbia’s average flows today.

Lake Missoula’s water, all 550 cubic miles of it, drains in 55 hours — less than three days — according to the model. At that time, the flood surge peaks in the Columbia Gorge at The Dalles, rising 950 feet above river level (1,000 feet above sea level), spilling over the gorge walls in places, and flooding the valleys of tributaries for miles upstream.

Inundation of the Willamette Valley peaks on the seventh day after dam burst, in the simulation. Flooding reaches as far south as Eugene. Loaded with mud and gravel, the flood dumps sediment across the entire valley. Repeated floods build a layer 100 feet thick in Woodburn.

Such a vast inundation, far greater than anything ever witnessed in historical time, seemed impossible to geologists in the 1920s, when J Harlen Bretz proposed that the scablands resulted from a catastrophic flood, not eons of gradual erosion. The idea didn’t gain mainstream acceptance until the 1960s. Since then, geologists have found evidence that Lake Missoula emptied catastrophically dozens of times during the last ice age.

But controversy persists. A few scientists assert that the cataclysmic floods must have had multiple sources, not just an outburst from Lake Missoula. John Shaw of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, for instance, has proposed that an enormous reservoir beneath the ice sheet over much of central British Columbia boosted the flooding.

The new simulation suggests that discharge from Lake Missoula alone would have been powerful enough. The simulated flood reaches peak stages all along its route that match the evidence visible today in sediment, with one big exception: At Wallula Gap, water levels in the simulation fell short by as much as 130 feet.

“It’s pretty clear, if Lake Missoula is enough to hit all the other high water marks, you don’t need another source of water,” Denlinger said. Calculating the convoluted paths of such a massive flood requires an immense amount of number crunching. Simulating one flood requires more than 8 months of computer time, Denlinger said.

But the computer simulation isn’t likely to end the debate. The fact that it can’t reproduce the maximum flooding at Wallula Gap leaves room for doubts. And some experts say there is direct evidence for an additional source of flood waters from beneath the ice sheet that covered the Okanagan Valley.

“It is conceivable that other valleys in southern British Columbia contributed water to the scablands but the field evidence necessary to test these possibilities has not been fully documented,” said earth scientist Jerome-Etienne Lesemann at the University of Aarhus in Denmark.

“There are a number of unanswered questions,” he said. “That makes the whole Channeled Scablands story a really interesting and intriguing geological puzzle.”

Reprinted from The Oregonian, original article by Joe Rojas-Burke, 2010