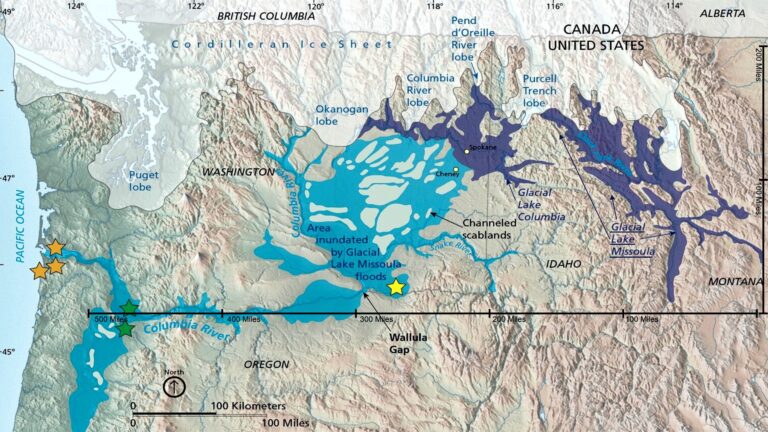

During the most recent Ice Age (18,000 to 13,000 years ago), and probably in previous Ice Ages, cataclysmic floods inundated portions of the Pacific Northwest. These Ice Age Floods originated primarily from Glacial Lake Missoula, but also from Lake Bonneville and perhaps as sub-glacial outbursts from under the continental ice sheet.

When part of that Cordilleran Ice Sheet pushed into the Lake Pend Oreille area of the Idaho Panhandle, it created an ice dam over 40 miles wide and 3000 feet thick, that blocked the Clark Fork River drainage and impounded Glacial Lake Missoula. At its largest, the lake was more than 2,000 feet deep at the ice dam and held over 500 cubic miles of water—as much as Great Lakes Erie and Ontario combined.

Eventually the impounded lake water broke through the ice dam, sending a towering mass of water and ice, up to 1000 feet deep, sweeping across parts of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon on its way to the ocean. The huge lake likely emptied in as little as two to four days. With a peak flow rate ten times the combined flow of all the current rivers of the world, the floods stripped and locally redeposited downstream as much as 50 cubic miles of sediment and bedrock, and created the astounding landforms that still attest to this story.

Over a period of years after each flood, the ice sheet would readvance, once again damming the river and causing the lake to reform. This process repeated scores of times, perhaps every 40 to 140 years, until the ice sheet ceased its advance and receded northward at the end of the Ice Age.

Recent research has found evidence that comparable floods occurred much earlier in the Ice Ages in the Columbia Basin, as much as 1 to 2 million years ago. These floods are a remarkable part of the North American natural heritage that have profoundly affected the geography and ways of life in the region, but have until recently remained largely unknown to the general public.

It has been determined that huge Ice Age glacial-outburst floods have occurred in other parts of the world, as well. Even in our own times, similar but much smaller outburst floods have occurred in several areas. Scientific study of the Ice Age Floods is contributing to the understanding of cyclical climate change and of very large and destructive contemporary floods on Earth. The Ice Age Floods have also been considered as an analog to understand geologic processes on Mars, where land-forms strikingly similar to those in Eastern Washington exist.

Could huge floods on this scale happen again?

With global warming now a serious concern, there is also concern that failures of the Antarctic Ice Sheet may produce cataclysmic sea level changes. Farther in the distant future it is likely that long-term climate cycles will cause large ice sheets to return at some time, and that similar cataclysmic outburst floods may recur, possibly even in this region.

Early settlers in eastern Washington State recognized that the landscapes were different than those seen in other places but were not sure why.

A closer examination of the features in the Basin led one geologist, J Harlen Bretz, to propose that only a sudden cataclysmic flood, on a scale never before considered possible, could account for the phenomenal size and distinctive characteristics of the land-forms.

This radical idea was not well received by fellow geologists, and a long-running scientific dispute followed.

In 1923 Bretz published the first in a series of scientific papers in which he proposed that the severely eroded Channeled Scabland, Dry Falls, and other immense geologic features had been formed by huge, powerful floods that had swept through the Columbia Basin.

Despite his peers’ doubt and opposition, he resolutely maintained that direct examination of the geologic evidence could lead only to that conclusion, but Bretz was unable to identify the source or cause of such catastrophic flooding.

Bretz used the name “Spokane Flood” because he assumed the source of the water for his “outrageous hypothesis” was somewhere near Spokane, Washington. But earlier, in 1910, another geologist, Joseph T. Pardee, had described evidence of a great ice dammed lake, Glacial Lake Missoula, that had formed during the Ice Age in northwestern Montana.

In 1925, Pardee suggested to Bretz that a collapse of the ice dam holding back Lake Missoula would have unleashed a mighty flood. However, Bretz didn’t see the connection between the glacial lake in Montana and the features he described in eastern Washington.

Then, in 1940, Pardee reported on his discovery of giant ripple marks, 50 feet high and 200-500 feet apart, that had formed on the floor of Glacial Lake Missoula. These huge, current-related features, along with other newly found land-forms, dramatically confirmed that the lake had suddenly emptied to the west, unleashing the tremendously powerful erosive forces that shaped many of the land-forms found in the Columbia Basin.

More research followed, and new perspectives became available from aerial photography that conclusively established that many extraordinarily huge and powerful Ice Age Floods had shaped the region. Among geologists, the concept of a catastrophic flood came to be accepted by the late 1950s.

The National Park Service is happy to share a curriculum guide to teaching the Ice Age Floods, “Investigating Ice Age Floods.” We are so glad you’re joining us on this journey of discovery. This educator’s guide provides adaptable lesson plans and other resources to help you engage students with the forces that created our dramatic landscapes.

This includes the most recent Ice Age Floods some 18,000 to 15,000 years ago, which crossed Montana, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon, as well as the forces that created the rocks they eroded and more.

Students experiment with scientific phenomena, ask questions, analyze and interpret data, construct explanations, engage in argument from evidence, and obtain, evaluate and communicate information. In short, they get to be scientists as they explore the awe-inspiring phenomena of our Northwest (NW) landscapes and the processes that created them through hands-on investigations, field studies, and other engaging projects.

Here is a link to the curriculum guide – Investigating Ice Age Floods -Teachers Guide