Two tiny pterosaur fossils, each smaller than a mouse, have finally solved a puzzle that has mystified paleontologists for decades. The perfectly preserved hatchlings, nicknamed “Lucky I” and “Lucky II,” were discovered in Germany’s famous Solnhofen limestone formations and reveal both how they died and why juvenile flying reptiles dominate this fossil record.

The Tragic Discovery

Both Pterodactylus hatchlings, just one to two weeks old when they perished, share a telling characteristic: broken wing bones with identical fracture patterns. The clean, slanted breaks to their humerus bones suggest the same type of twisting force killed them both 150 million years ago.

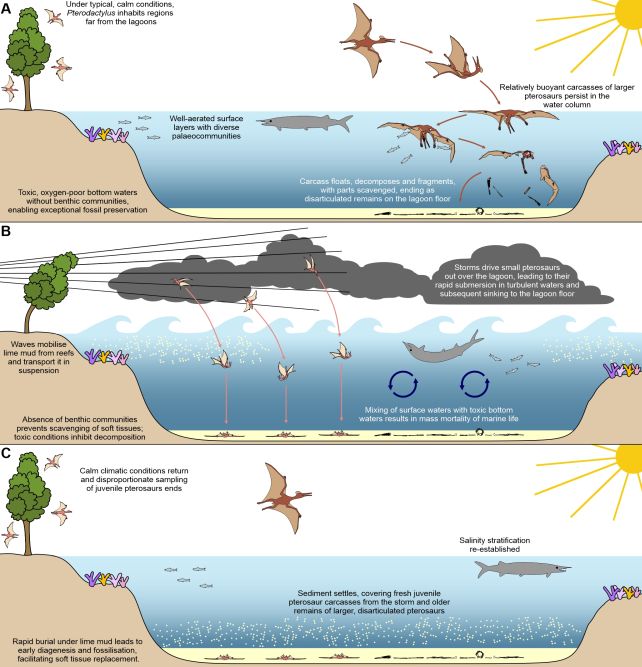

University of Leicester paleontologist Rab Smyth and his team reconstructed their final moments through careful forensic analysis. The evidence points to a violent Late Jurassic storm that battered the tiny pterosaurs with winds so powerful their fragile wing bones snapped under pressure. The same storm then hurled their bodies into a saltwater lagoon, where churning waters quickly carried them to the bottom for rapid burial and exceptional preservation.

Solving the Solnhofen Paradox

Solving the Solnhofen Paradox

The discovery resolves a long-standing mystery about the Solnhofen formations, which contain hundreds of pterosaur specimens but are dominated by juveniles. This seemed counterintuitive since young pterosaurs had more fragile bones and should be less likely to fossilize than adults.

The research reveals this apparent contradiction actually makes perfect sense. The same catastrophic storms that killed vulnerable hatchlings created ideal conditions for their preservation. Adult pterosaurs, being stronger and more experienced, could survive the violent weather that proved fatal to their offspring. When adults eventually died under calm conditions, their remains would float and decompose before sinking, making fossilization unlikely.

“For centuries, scientists believed that the Solnhofen lagoon ecosystems were dominated by small pterosaurs,” Smyth explains. “But we now know this view is deeply biased. Many of these pterosaurs weren’t native to the lagoon at all – they were inexperienced juveniles caught up in powerful storms.”

Broader Implications

This discovery transforms our understanding of pterosaur ecology and fossil preservation. Rather than reflecting true population dynamics, the juvenile-heavy fossil record represents a preservation bias created by extreme weather events. The findings also provide rare insight into Late Jurassic climate patterns, suggesting violent storms regularly impacted ancient ecosystems.

The research exemplifies how modern paleontology combines traditional fossil analysis with environmental reconstruction. By examining preservation circumstances alongside the bones themselves, scientists can extract far more information from specimens and avoid misinterpreting ancient ecosystems.

Published in Current Biology, this work offers a new framework for understanding how environmental factors influence fossil records – reminding us that every preserved specimen tells a story not just about the creature’s life, but about the dramatic events that led to its preservation across deep time.

AI adapted from Original reporting by Michelle Starr, ScienceAlert about research by Rab Smyth and colleagues, University of Leicester..